A renewed battle for corporate transparency in Europe [Video]

Late last year, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) invalidated one of the most important anti-money laundering provisions of recent years – that of public access to beneficial ownership (BO) registers in the EU.

Lawyers for plaintiffs in the cases that led to the ruling appear to have presented a hypothetical scenario in which a person’s safety was threatened because they appeared as the real owner of a company in a public register. The ruling considers public access to such a register a serious infringement of the plaintiff’s rights to privacy and protection of their personal data. Never mind that an individuals’ connection to a company is frequently already public knowledge. Never mind that there have yet to be any instances of BO registers being exploiting to to commit crimes against company owners. And never mind that beneficial ownership registers do not contain information about the assets held by a company, its solvency, revenue or profitability.

Experts have denounced the ruling as ‘perverse.’ There is a real irony in a human rights argument (that of privacy) being used to protect the wealthy from scrutiny and – by making it easier to hide illicit wealth – negatively impacting the rights of poor and marginalized populations.

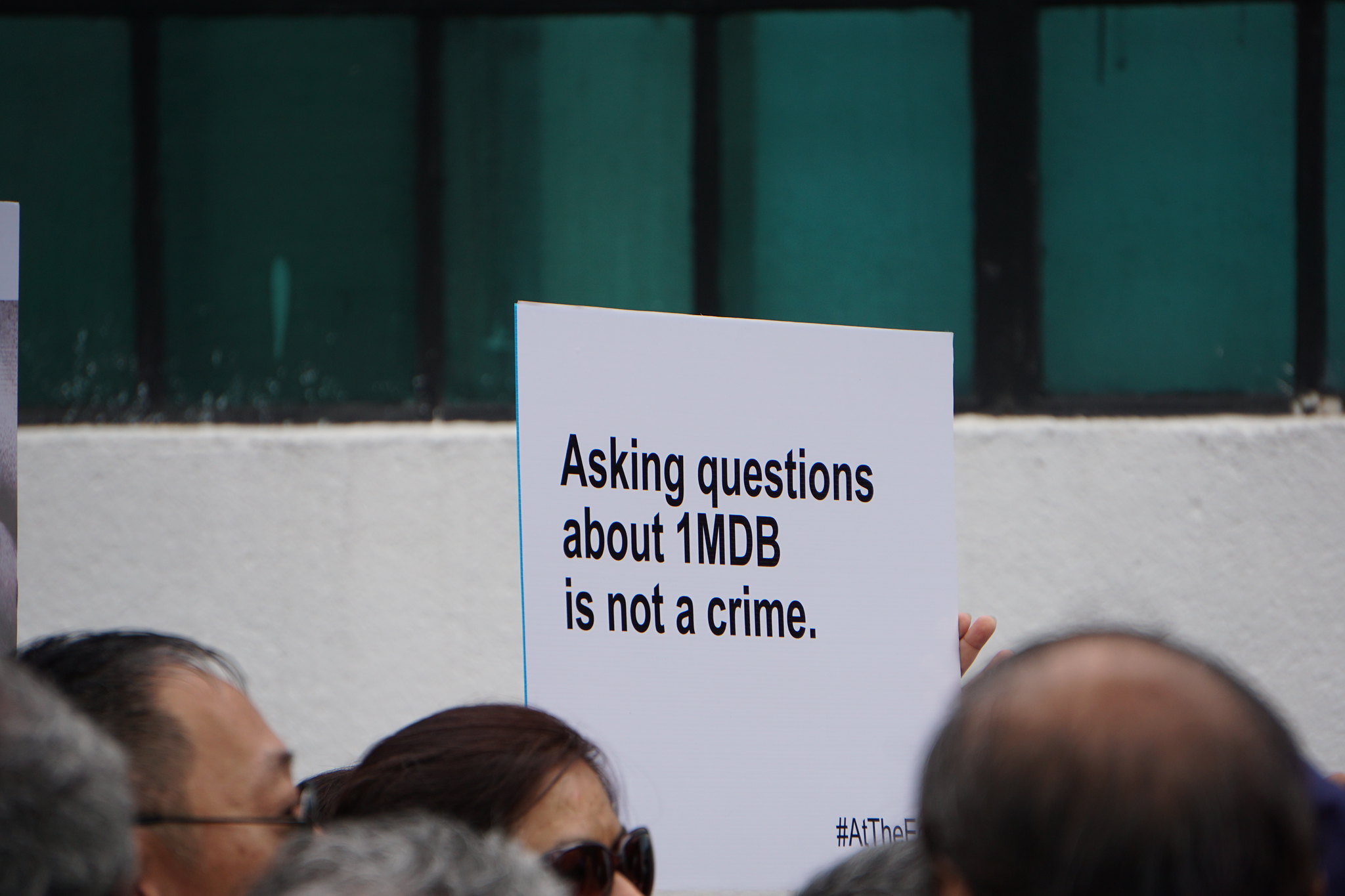

Public BO registers have been a game-changer for anti-corruption investigations by the media and civil society organizations. But, as transparency advocates are quick to point out, it isn’t just NGOs and investigative journalists who have made important use of easily accessible data. Financial intelligence units often prefer to use other countries’ public registers rather than engage in complicated requests for mutual legal assistance with their counterparts abroad. Banks, lawyers, notaries and other businesses all use these registers to conduct legally required due diligence on their clients.

Public access is not only more efficient for these diverse user groups – it is more efficient for the authorities managing the registers themselves. Evaluating individual requests for access will tie up resources that should be spent on verifying the information in the register, as well as enforcing violations for false, incomplete, or misleading entries. For registers to be useful for law enforcement and other authorities investigating money laundering, tax evasion and financial crimes, officials must have the time and tools to ensure that the information they contain is accurate. It is difficult to imagine that this point is lost on the plaintiffs and their lawyers.

The ruling does recognize the role of civil society and media in accessing beneficial ownership information. Governments need to work out quick, easy and unfettered access for everyone with a role in fighting financial crime and corruption everywhere.

This needs to include academic researchers and data scientists. Big-data analyses of registers can pinpoint policy and implementation loopholes, directing policymakers to both successes and areas for improvement. ACDC’s In the Dark report with Transparency International, using data scraped from the Luxembourg public register, is a case in point. The report found that up to 80 percent of funds in Luxembourg’s $5.4 trillion private investment industry had not declared their end owner due to weaknesses in the definition of beneficial owner. The United Nations University also recently funded work by ACDC members to analyze the impact of the UK’s Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Bill. This would be impossible without regular, unfettered access to the public register of overseas beneficial owners of UK properties that the bill created.

Access must also be granted in a way that avoids tipping off the subjects of investigations that someone is looking into companies’ ownership structure. The sad reality is that two investigative journalists have been killed in EU countries in recent years in nefarious attempts to silence their work revealing interconnected networks of organized criminals and corrupt officials. If outed, journalists or organizations digging into complex and opaque corporate structures can face intimidation, harassment and push-back against their public-interest reporting and advocacy.

Sadly, however well or badly governments respond to the new challenge of assessing and granting access, taxpayers will have to foot the bill – either by funding an agency to manage processes that needn’t exist, or through money lost to corruption, tax fraud and other financial crimes.

Investigative journalists looking into financial crimes have generated phenomenal financial returns for society. The Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project has calculated that its work has contributed to $9.6 billion in fines and monies seized since 2011. The Panama Papers investigation alone – based on leaked data and predating public BO registers in the EU – has helped governments around the world recoup over $1.2 billion. The potential net economic gain of having beneficial ownership information in the public domain is enormous.

Corporate vehicles in the EU are attractive for corrupt officials from all over the world, allowing them to easily purchase assets, make investments and establish influence in Europe, using money stolen from the public purse at home. Meanwhile, Europe is investing in sustainable development in the same countries, seeking to promote transparency, the rule of law and strengthen anti-corruption agencies, civil society and independent media: the same people who just had the rug pulled from under their feet.

The incoherence of this ruling with established and agreed policy is part of what makes it so baffling. EU governments, and their partners in the G7, must work with transparency advocates to find a solution. They mustn’t stand by while the rhetoric of human rights is abused to roll back progress that has led to the head of a European government being exposed in a massive conflict of interest, exposed Putin’s cronies’ European assets, and made the EU the standard-bearer for a new era of corporate transparency.

Until recently, this progress had been successfully balanced with leading the charge on data privacy and protecting the public’s rights over their data. That balance was, in principle, achieved by protecting the public’s rights against corporate interests.

The ECJ’s ruling reverses that logic.