A veil of opacity leaves Sovereign Wealth Funds susceptible to corruption

In a new volume edited by Jodi Vitorri and Lakshmi Kumar, ACDC co-founder David Szakonyi draws attention to the opacity surrounding Sovereign Wealth Funds (SWFs). For many countries around the world, SWFs present a tremendous opportunity to advance their development agendas through investments in public and private markets. Worldwide, SWFs control a whopping $11.5 trillion in assets. However, as multiple cases have shown, these state-owned and government-controlled funds are also highly susceptible to corruption, including embezzlement, fraud, and political exploitation. At the heart of the problem is a profound lack of transparency and accountability, which severely restricts access to reliable, comprehensive data.

The veil of opacity over Sovereign Wealth Funds

As state-owned and -controlled investment vehicles, SWFs are in some ways distinct from the highly opaque private investment funds which have been a priority area for the Anti-Corruption Data Collective since we launched in 2021.

SWFs are more patient and passive investors than many private funds, and often aim to achieve broader goals through their investments, such as macroeconomic stability or domestic economic development, beyond merely maximizing investment returns.

Yet at the same time, SWFs often share structural similarities with hedge funds, venture capital, and private equity, with external partners managing the committed capital. Moreover, much like the private investment fund sector, there is extremely limited public knowledge about the investments, operations, or internal management of most SWFs. The absence of detailed financial and operational transparency creates a fertile ground for unethical managers and political elites to siphon off investment returns.

Contrary to common perceptions, many SWF investments do not flow into publicly traded companies. Instead, similar to their private counterparts, SWFs frequently acquire minority stakes in unlisted, privately held firms. In most jurisdictions, these non-public market transactions are subject to minimal transparency requirements from investment funds, and that includes SWFs. For example, in the United States, SWFs have to publicly disclose equity holdings of five per cent or more in publicly traded firms, but there is no such requirement for investments in privately held companies. With few exceptions, SWF investments in non-public assets, whether in private companies or real estate projects, are not publicly disclosed.

The overlap between SWFs and private investment funds is further highlighted by the fact that SWFs increasingly invest directly in private equity. SWFs now rank among the top institutional investors in private equity globally. Between 1984 and 2007, twenty-nine SWFs made over 2,500 direct private equity investments, totalling $198 billion. In the aftermath of the 2007-2008 financial crisis, SWFs have even started accruing substantial debt to finance investments—a strategy common in the private equity sector.

Challenges in data availability

Following and mimicking private markets means entering the same highly opaque territory. The result is that regulators, journalists, civil society activists, academics, and investors interested in the operations of many SWFs are left with scant information, just as we are when we investigate private investment funds. The limited data that are available are often incomplete and prohibitively expensive for most researchers. Analysts typically rely on third-party aggregators such as PitchBook, Preqin, and FactSet, which offer comprehensive but costly data services. These high subscription costs hinder law enforcement and regulatory authorities’ ability to track SWF financial flows, increasing financial and logistical challenges for conducting due diligence.

The problem is compounded by the fact that these third-party aggregators depend heavily on SWFs voluntarily sharing underlying data. If a SWF, particularly one in a non-democratic nation, opts not to disclose an equity investment, it is unlikely that any aggregator will pick up that activity. Significant portions of SWF portfolios, such as bond markets and domestic assets, remain largely opaque.

Whistleblowers to the rescue?

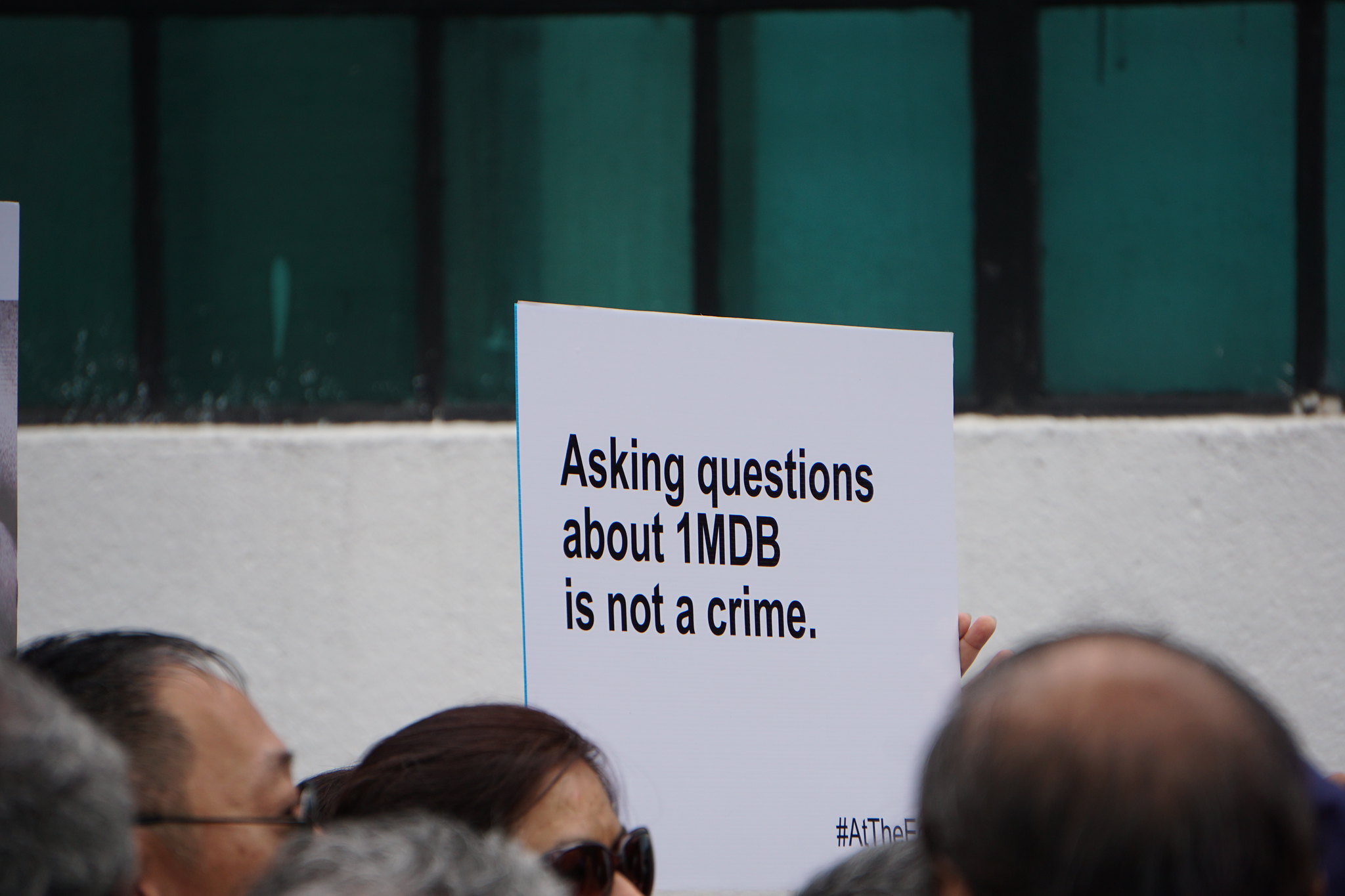

We do occasionally get an insight into SWF operations through leaks of internal documents. The 2018 Paradise Papers leak exposed extensive cronyism and corruption within Angola’s SWF, the Fundo Soberano de Angola. The fund paid millions in management fees through uncompetitive tenders to investment managers linked to the country’s ruling elites. Even supposedly well-governed funds have faced scandals following document leaks. Internal documents from Australia’s Future Fund led to accusations of tax avoidance and exorbitant fees to external managers.

Global Witness received a leak of internal fund documents from the Libyan Investment Authority (LIA), which revealed how Muammar Gadaffi and his family had managed the fund’s $64 billion. A later audit by Deloitte suggested that upward of 20 per cent of the LIA’s value had disappeared into a black hole, presumably lining the pockets of the ruling elite. Accusations were also leveled at Goldman Sachs, whose investment managers were accused of paying prostitutes and buying private jets and stays in five-star hotels in an attempt to woo business from the LIA.

However, such leaks rely on whistleblowers, who often face enormous personal risk and cannot always share a comprehensive picture of a fund’s activity. Leaks are a welcome but highly imperfect mechanisms for ensuring transparency.

More transparency, more accountability

To foster accountability, SWFs must be required to disclose extensive and detailed information about their strategies, asset management, executive compensation, and engagements with financial intermediaries. Such transparency is crucial for making SWFs accountable to their public constituents.

SWFs should disclose fundamental financial data, including assets under management, performance indicators, market allocations, benchmarks, and ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) metrics. Ideally, these disclosures would be validated through external audits. The broader pooled investment industry, which faces similar opacity and risks, should also adhere to these transparency standards.

Organizational disclosures should include key policy objectives, governance structures, board selection processes, and relationships with policymakers and regulators. Enhanced reporting mechanisms and increased roles for elected legislatures and independent agencies are essential for ensuring investments serve the national interest. Effective transparency allows stakeholders to act on disclosed information, preventing the politicization of SWFs. Voluntary disclosure alone is insufficient; mandatory comprehensive disclosure is imperative.

By lifting the veil of secrecy, SWFs can significantly improve their governance and accountability, ensuring they effectively contribute to their nations’ economic stability and development.