Large Political Donations Came After Paycheck Protection Program Loans

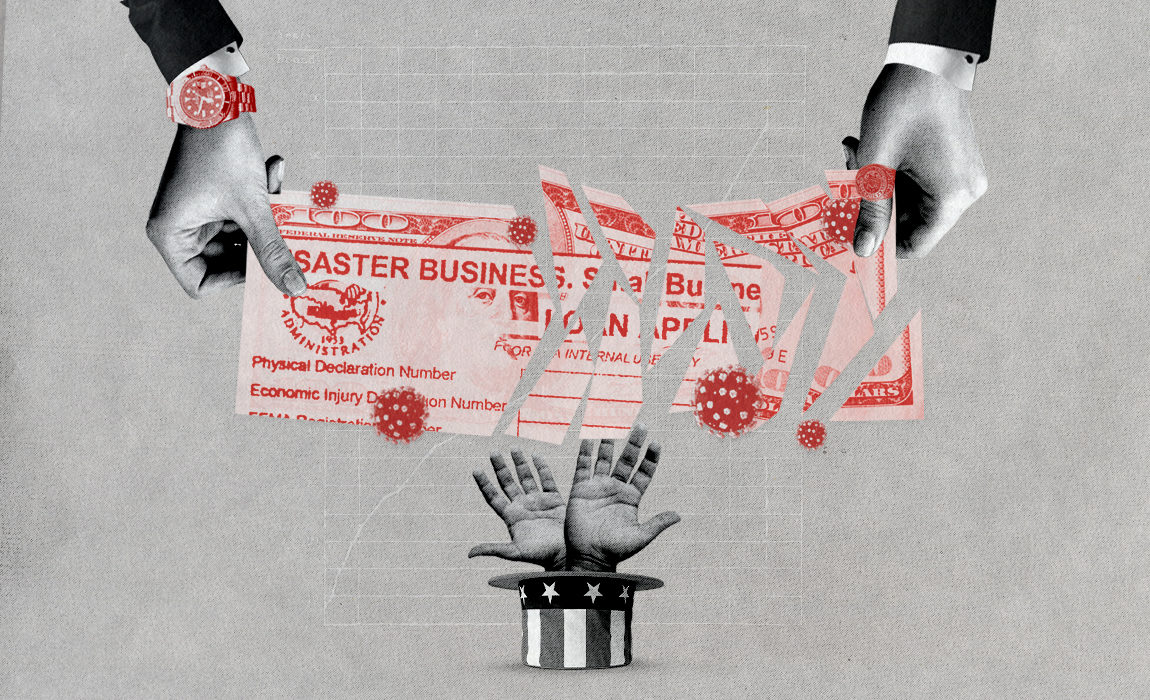

Large political donations flowed from over a hundred businesses after they received taxpayer-backed pandemic loans, according to an analysis of federal data by the Project On Government Oversight (POGO) and the Anti-Corruption Data Collective. The donations suggest that many of these recipients might not have truly needed the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) funds meant for struggling small businesses. In a handful of instances, political candidates received large donations after companies they controlled, or companies owned by family members, obtained loans.

The owner of at least one PPP loan recipient who then donated to political candidates has been charged with fraud, although the charges do not appear connected to the contributions. One member of Congress returned political donations from that accused fraudster and other executives at his company.

POGO and the Anti-Corruption Data Collective identified at least 113 loan recipients that obtained a total of between $136 million and $305 million in PPP loans, where either the companies or company owners subsequently made political donations of at least $25,000. In the wake of PPP loan approvals, the owners or the companies made a collective 163 political contributions worth approximately $11.7 million, with one donation worth $2 million. The contributions went to candidates from both political parties, Federal Election Commission data shows.

All Paycheck Protection Program loan applicants were required to certify that “current economic uncertainty makes this loan request necessary to support the ongoing operations of the Applicant.” So political gifts by the recipient-companies or their owners raise many questions, such as whether, if they could be so generous in their political giving, they truly needed taxpayer-backed financial lifelines. It also is not clear if recipients funneled any of the loan money directly to political contributions or if the loans may have freed up funds to do so.

Another question is whether the Small Business Administration (SBA), which administers the program, and federal law enforcement see significant political giving by loan recipients or by the companies’ owners as warranting greater scrutiny. And it remains to be seen whether Congress will strengthen oversight or tighten loan eligibility requirements if it approves more coronavirus relief for small businesses.

The largest single donation by a Paycheck Protection Program recipient-company’s owner identified by POGO and the Anti-Corruption Data Collective came from Geoffrey H. Palmer, a major Republican Party donor. On April 30, his real estate firm G.H. Palmer Associates was approved for a Paycheck Protection Program loan of $350,000 to $1 million. Just over a month later, on June 5, Palmer poured $2 million into America First Action, a pro-Trump Super PAC. G.H. Palmer Associates did not respond to a request for comment.

Then there’s the case of Hollywood mogul Joseph E. Roth, whose film and TV production company co-produced 2010’s Alice in Wonderland, which grossed over $1 billion. On April 10, Roth Films, Inc. was approved for a Paycheck Protection Program loan worth between $150,000 and $350,000. On April 30, Roth donated $250,000 to the Save America Fund, a Super PAC dedicated to opposing Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY). (McConnell easily won reelection.) Roth was the largest contributor to that Super PAC. A spokesperson for Roth’s business manager—whose address was listed on the Federal Elections Commission record for the donation—told POGO that the manager’s firm does “not comment on clients” and did not respond to a question asking for contact info for someone who could comment.

Robinson Calcagnie, Inc., a Newport Beach, California, law firm specializing in personal injury and wrongful death cases, was approved for a Paycheck Protection Program loan worth between $1 million and $2 million in April. Its founder and “sole shareholder,” attorney Mark P. Robinson Jr., donated $100,000 to the Biden Victory Fund Super PAC and $35,500 to the Democratic National Committee in June. Robinson did not respond to POGO’s request for comment.

Another example involves a set of related pipeline construction companies in Texas that share an address. In late April and early May, US Trinity Energy Labor Services LLC and US Trinity Energy Services LLC were each approved for Paycheck Protection Program loans worth a total of between $5.35 million and $11 million. On June 18, US Trinity Holdings LLC donated $250,000 to the Trump Victory Super PAC. U.S. Trinity did not respond to POGO’s request for comment.

Paycheck Protection Program loan “recipients should have been prohibited from making political contributions,” Robert Weissman, president of the nonprofit Public Citizen, told the Huffington Post.

Such a prohibition, especially if it’s broad, could run afoul of the First Amendment.

Although federal law bars federal contractors from contributing to political campaigns, contractor executives, employees, and individual owners of company stock can make contributions from their own personal funds. A Congressional Research Service report from September notes that in 2015 a federal appeals court upheld this limited ban because it serves the “‘sufficiently important’ government interest of guarding against quid pro quo corruption and its appearance, and protecting merit-based administration of federal contracts.”

But the merit-based administration of federal contracts is different from an emergency loan program meant to help virtually any kind of small business facing economic turbulence. Over 5.2 million businesses were approved for Paycheck Protection Program loans.

Even if a ban on political giving by Paycheck Protection Program loan recipients is off the table, that does not preclude the federal government from asking hard questions before forgiving these loans and scrutinizing recipients for having potentially misled lenders about their financial needs.

“Will you commit to returning that money to the citizens?”

In some cases, candidates received political donations from their own companies, or those owned by family members, after obtaining Paycheck Protection Program loans.

One example is Taylor Commercial, a construction company owned by House Representative-elect Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA) and her husband. The company donated $700,000 to her campaign in the months after receiving a Paycheck Protection Program loan worth between $150,000 and $350,000. That donation was in addition to a prior $450,000 gift to her campaign before the loan came in. Greene has gone on the record opposing coronavirus relief spending.

Her Republican primary opponent raised the issue over the summer. “You said that you didn’t want Congress to pass more COVID-related emergency funds for businesses. But your business took as much as $350,000 in PPP loans from the federal government at the same time you were putting $900,000 into your campaign,” John Cowan told Greene during a July debate. “So if you don’t need the money and you have the discretionary funds, will you commit to returning that money to the citizens?” She didn’t directly answer Cowan’s question, but said, “I have a construction company and we can’t do construction remotely at home.” Taylor Commercial’s service area spans ten states across the South with varying levels of restrictions during the pandemic. Her campaign did not respond to a request for comment.

Along with the example of Greene, Salon reported on several other cases of candidates donating to themselves after their family-owned businesses received relief loans. Derek Martin with the progressive watchdog group Accountable.US told Salon, “The PPP program was meant to save jobs, not bail out business owners looking for a gig in D.C.”

Companies owned by wealthy lawmaker Representative Vern Buchanan (R-CA) received $7 million in loans before he donated $250,000 to his own campaign. Buchanan’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

A returning member of the House, Darrell Issa (R-CA), who may again be the wealthiest legislator with a net worth of more than half a billion dollars, loaned $150,000 to his own campaign in May, soon after his company Green Properties, Inc. obtained a Paycheck Protection Program loan worth between $150,000 and $350,000, as first reported by La Prensa San Diego. Issa would contribute another $950,000 to his campaign in September. In response to an attack ad citing the PPP loan, Issa said at a news conference in October that “No funds were transferred from Green Properties to any of the accounts of Darrel and Kathy Issa in May, June, July or August” and that any allegations to the contrary are “outright lies.”

Criticism of political donations by Paycheck Protection Program loan recipients has come from both ends of the political spectrum.

In Texas, Republican attorney Mark McCaig raised the issue of four Houston-based law firms donating to a pro-Democratic PAC called First Tuesday shortly after they received Paycheck Protection Program loans. He analyzed state-level campaign contributions disclosed to the Texas government, rather than contribution data disclosed to the Federal Election Commission that POGO and the Anti-Corruption Data Collective reviewed.

“The fact that these law firms had ample financial resources on hand to make generous political contributions just weeks after receiving ‘Paycheck Protection’ loans warrants investigation by the Small Business Administration into whether these law firms made truthful certifications about the necessity of the loans to support their operations,” McCaig wrote.

That business owners participated in the most expensive election season ever by making campaign contributions is not on its own surprising. But for owners of some companies that made contributions, the scale of their political giving, in close proximity to receiving loans that were meant for small businesses without ready access to capital, could draw scrutiny from federal investigators looking for instances where loan applicants misled banks and the Small Business Administration about their financial state and economic need. However, large political contributions after receiving a Paycheck Protection Program loan aren’t enough evidence on their own to lead to criminal prosecution.

Cases based on challenging whether a loan recipient was in genuine financial need may be hard for federal law enforcement to pursue criminally, according to Lee Bacon, a special agent with the Small Business Administration’s Office of Inspector General, who spoke at a recent George Washington University Law School event on fraud in pandemic relief programs. He responded to a question from POGO on whether loan recipients that did not financially need a Paycheck Protection Program loan could be prosecuted for fraud.

Criticism of political donations by Paycheck Protection Program loan recipients has come from both ends of the political spectrum.

Because the loan “application itself doesn’t collect specific documents or data that prove that the loan was required due to economic uncertainty,” Bacon said, “solely from the perspective of pursuing that criminally, it’s going to be difficult after the fact to claim that there was some false information provided beyond indicating that there was economic uncertainty.”

“You could arguably suggest that a company whose revenues increased … was not dealing with economic uncertainty,” he said, but “I could not speak to how palatable that argument would be to a federal prosecutor.”

“I’m not familiar to date with any specific criminal referrals that have been based on economic uncertainty,” he said.

Still, if a loan recipient misused money primarily meant to pay workers and made false statements to obtain the funds, it shouldn’t matter whether they spent the money on Lamborghinis or to make lavish campaign contributions. And the SBA’s examination of economic necessity is just getting off the ground, which could explain the lack of criminal referrals. As the law firm Crowell & Moring LLP noted last week, “the SBA is beginning to undertake an information collection effort to allow SBA loan reviewers to scrutinize a borrower’s certification that economic necessity made the loan request necessary.” An SBA questionnaire asks recipients of PPP loans over $2 million if the company’s owner or anyone else at the company received compensation above $250,000. This suggests that SBA may examine whether recipients needed a PPP loan or forgiveness if owners are flush with financial resources.

But unless there’s evidence that a loan recipient was not operating in good faith when they certified that they faced economic uncertainty, a recipient is probably safe from criminal sanctions.

And even if a recipient was acting in bad faith, POGO’s review of the first six months’ worth of Paycheck Protection Program fraud cases brought by the Justice Department shows that usually some other element of apparent fraud is present when the department has brought charges, such as faked tax records or doctored payroll documentation.

“I … Don’t … Care.”

At least one loan recipient who made campaign donations to members of Congress after receiving millions in Paycheck Protection Program dollars has been charged with fraud, although Justice Department court filings do not mention the contributions, nor do the charges relate to them. The post-PPP loan contributions are also less than $25,000. The criminal complaint against Martin Kao, CEO and “99%” owner of Navatek LLC (recently renamed the Martin Defense Group), alleges that he cited correspondence with members of Congress and their staff when communicating with a bank while trying to obtain a $10 million Paycheck Protection Program loan.

“I just got off a couple calls with [a U.S. Senator and Member of Congress]. The [sic] specifically asked about the status of our PPP loan application and were very adamant about stepping in, if our application was getting stalled,” Kao emailed Central Pacific Bank (CPB) on April 7, according to the criminal complaint. He continued to cite his communications with Congress, asking for the name of the person who made loan approval decisions at the bank. “Who is the person(s) at CPB? Is he/she willing to get onto a call with Congress? They will be happy to make it unequivocally clear what the rules are,” he wrote in an April 10 email.

The Justice Department filing does not name the senator or the other member of Congress and does not state if Kao actually was in communication with Congress regarding his loan or if it was just bluster. Other emails from Kao cited in the complaint refer to the senator and “a senior staff member of a U.S. Senator.”

“[The Senator] is suggesting a conference call with his Banking Committee and SBA staff director … SHE HELPED WRITE THE PPP RULES,” Kao stated in another email to Central Pacific Bank on April 10 where the text is underlined, according to the criminal complaint. “She has confirmed directly that CPB should and is obligated to fund once SBA issues the approval number. Any additional review the bank does should be perfunctory … at best.”

A week later, Central Pacific Bank approved a $10 million Paycheck Protection Program loan for Navatek—the maximum available. Kao then secured a second loan, worth $2.8 million, from another bank. His attempt to obtain more loan money failed when a different lender discovered that Kao’s company had already been approved for a loan and the program only allowed one per recipient.

A former Navatek executive told federal law enforcement that he “did not believe” that “Navatek was suffering financially as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Whether that was the case or not, after Navatek was approved for its first and biggest PPP loan, Kao made political contributions. He gave $2,800 to Senator James Inhofe (R-OK) on April 24. Inhofe does not serve on the Senate banking committee, referred to in Kao’s emails, but he is a member of the Senate Small Business Committee, which oversees the Small Business Administration and the Paycheck Protection Program. On August 19, Kao gave the same amount to Representative Derek Kilmer (D-WA) as well as to Kilmer’s leadership PAC called Defense Economic Renewal Education & Knowledge, or DEREK.

A spokesperson for Inhofe told POGO, “Our office has not talked with Navatek about PPP and supports the full prosecution of Mr. Kao.” Kilmer’s campaign told POGO that “Neither Congressman Kilmer nor anyone from his office – campaign or official – ever had any discussion with Mr. Kao, Navatek, or the Martin Defense Group related to the PPP program” and that “immediately upon learning of the issues with Mr. Kao, all related donations to both the campaign and the leadership PAC were immediately refunded.” Kilmer’s spokesperson supplied POGO with links to Federal Election Commission filings showing funds from Kao and other Navatek executives were returned. Inhofe’s office did not tell POGO if Inhofe’s campaign would be returning donations too, and neither responded to a question regarding their non-PPP communications with Kao or his company.

Before the pandemic, Kao, other Navatek executives, and an entity he’s allegedly connected to had made significant contributions to members of Congress on both sides of the aisle, particularly to senators who sit on the powerful Appropriations Committee, which directs federal spending, according to an investigation by the Honolulu Civil Beat, an online news outlet. One of those appropriators, Senator Susan Collins (R-ME), said in a statement last year that she “strongly advocated for the funding” of an $8 million Pentagon contract that went to Navatek, and she visited the company’s office in Maine. She included a quote from Kao in her Senate press release. Collins’ office did not respond to a query.

The Civil Beat also obtained an email Kao sent his employees earlier this year. “I am a man of few words when it comes to matters like COVID-19 and our Country’s response in directly dealing with the virus and its collateral effect,” Kao wrote. “I am a man of even fewer words when it comes to your personal fears, feelings or afflictions with regard to the virus during these times. In fact, I really only have three words: I … Don’t … Care.”

He continued, “What I do care about is ensuring that all of you have the knowledge and ability to take comfort that your jobs and finances are secure and the Company is positioned to continue to grow at an incredible pace, despite the impact of CV-19.”

A Navatek spokesperson told POGO that “the company’s focus continues to be on serving our clients and supporting our employees as we move our projects forward” and directed POGO to send queries to Kao’s personal attorney. Kao’s attorney did not respond.