Window or wall? Beneficial ownership and real estate data in France

Together with Transparency International (TI) and TI France, we’ve spent the better part of a year digging into French beneficial ownership and real estate data.

Our report, Behind a wall: Investigating company and real estate ownership in France finds that despite recent anti-money laundering reforms that increase transparency, we still don’t know as much as we should about who controls and who benefits from companies in France, especially those that own real estate.

Six years after France started collecting beneficial ownership information, more than a third of all companies registered in France have yet to declare any beneficial owner(s). In other words, we have no idea who owns a stunning 1.53 million legal entities operating in France, putting the companies in breach of France’s anti-money laundering regulations.

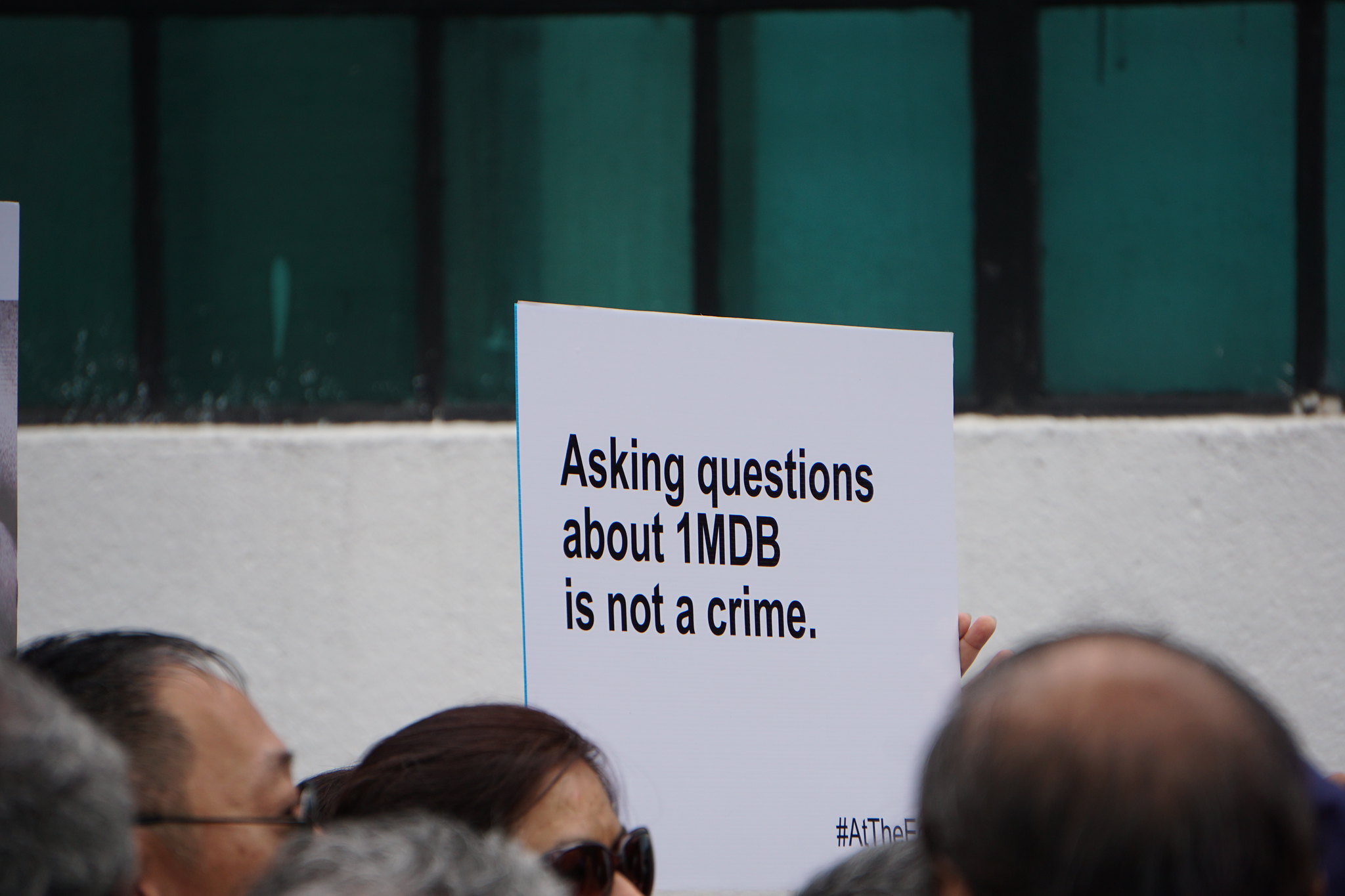

Our analysis further shows that over two thirds of all corporately held real estate in France belongs to a company with unknown beneficial owner(s). This is especially alarming since for years, we’ve seen how luxury French real estate, especially in Paris and the Riviera, has become a favorite destination for foreign kleptocrats, their relatives and cronies. And these revelations continue. The Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) has just unearthed more than a dozen properties in France linked to alleged money launderers, politicians accused of corruption and their relatives from across Latin America. While researching the report, we also identified 166 Russian persons of public interest with real estate in France: businesspeople, politicians, bureaucrats and their families, all owning properties ranging from ski chalets in the Alps to villas on the French riviera, to luxury apartments in central Paris.

In France, at least 10.35 million parcels of land – the smallest unit in the cadastre (or land plot plan) – are owned by private legal entities. The corporate owners of 3.66 million of those parcels appear in the company register, but have failed to declare their beneficial owner(s). More incredibly, companies that own another 3.92 million parcels do not appear in the company or beneficial ownership registers whatsoever.

Why is all this information missing?

The first reason is that foreign companies are allowed to own real estate in France without registering a French presence, which would then be subject to transparency requirements. Our partners at Transparency International have already flagged this loophole, which authorities should quickly close to stop criminals and corrupt skirting transparency requirements.

But the majority of these legal entities – a total of 717,411 companies that collectively own 2.42 million parcels – cannot be located in the company register because their unique nine-digit “SIREN” number in the database of parcels owned by legal persons appears to be entirely made up. These fictitious real estate numbers prevent anyone, whether it be a journalist, policy officer, or neighbor, from finding out who truly owns these properties. The French authorities have not yet clarified this almost preposterous development.

To be clear, there is still much that the rest of the publicly available data can tell us.

For instance, the use of Société civile immobilière (SCI), a common vehicle for owning real estate in France, stands out as particularly risky for money laundering. For years, the French authorities and the Financial Action Task Force have flagged SCIs as being at a heightened money laundering risk because their shares can be transferred without a notary, limiting the scrutiny over transactions. Yet we found that only 63 per cent of all SCIs have declared their beneficial owners, one of the lowest rates across all categories of corporate vehicles. Moreover, we could only identify beneficial owners for around half of all the SCIs owning real estate (1.3 million SCIs own 2.89 million parcels in France). Zooming in on Paris, no beneficial owner can be found for 72 percent of parcels owned via SCIs. For such a risky category of legal entities, the French government can and must do better in ensuring compliance with such a simple transparency requirement.

This high non compliance rate is compounded by other issues that make anti-corruption investigations and sanctions enforcement incredibly difficult.

First, the data on beneficial owners presented are static, providing only current information, but no records of changes submitted to the registry over time. This means that individuals expecting to come under scrutiny can disappear from the register by transferring ownership of their company to a relative, who may be harder to trace.

This tactic may have been used by Elizaveta Peskova, the daughter of Vladimir Putin’s spokesman, Dmitry Peskov. Peskova used to be listed as the beneficial owner of a company that owns at least one property in France. However, on 29 April 2022 – seven weeks after being sanctioned by the US – she transferred her shares in the company to her mother. Five weeks later, on 3 June 2022, she was sanctioned by the EU.

Accuracy is another huge issue. The same person can use different versions of their names, and even different nationalities, when they register their ownership of multiple companies in the register. These individuals may benefit from “Golden Passport” schemes, but only declare their newly acquired citizenship on the register. Our analysis also shows several instances of companies submitting an address that does not seem to physically exist or failing to report an address altogether. It is very unclear what steps the French government is taking to make sure that consistent, accurate information is included in the register.

We’re not the only ones to call the French beneficial ownership register into question. Open Ownership recently published a blog post summarizing the access and quality issues they encountered while attempting to map the INPI database to the Open Data standard.

France introduced an API for the register in early 2023 but the API limits calls to 10,000 per day. Re-doing the research for our report using just the API would take well over a year to download and scrape the entire database. Using a custom script, we were able to do it faster, but it still took more than a month to scrape roughly five million web pages.

It would be much better if France published its beneficial ownership data in a structured file. This isn’t about making our lives easier. The ability to compare data quickly and easily across different jurisdictions can make the difference between identifying a chain of ownership or flow of assets, or not.

On the face of it, France is one of the more transparent countries. Anyone can look up a private company or its beneficial owner in the register, for free, and use that information to verify the parties to a business transaction, conduct risk analysis and due diligence, or investigate potential illicit activity. Even after the EU Court of Justice ruling last year, France kept its register online and open to the public, while others suspended access or made journalists and civil society apply for access.

Yet if you evaluate the availability of data from a baseline of countries that are making better use of the potential, France unfortunately has a long way still to go. The authorities should focus attention on getting the compliance rate up, and work with civil society experts to improve the data collection, verification and publishing processes.

This report on France joins our previous big data analyses on Luxembourg, the US, and the UK. One of the lessons from this growing body of research is that regulation that embraces open access and ease of use in company and real estate ownership data ultimately is more effective. Together with Transparency International, we are now designing an index that will measure the adequacy of data availability and anti-money laundering rules for the real estate sectors of major economies and critical jurisdictions around the world. We also need more research that interrogates the data available, to understand if transparency measures are bringing much needed sunlight or if – as in France – important information for following flows of dirty money remains hidden behind a wall.

To manage the vast volumes of data required for this analysis, ACDC partnered with The Bright Initiative, using Bright Data Center Proxies to securely and efficiently gather the necessary data.